Midterm

The Case

On March 24, 1925, the Canton government in South China informed all oil dealers in Guangdong Province that, starting April 1, a stamp tax of twenty cents would be imposed on every five-gallon tin of kerosene. The Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang), which controlled the Canton government, was in urgent need of revenue. It had already imposed taxes on flour, tobacco, wine, sugar, and various other goods, including opium. Additionally, taxes were collected on slaughtered hogs, businesses, gambling, coffins, and shipping. Kerosene, however, remained untaxed and was seen as a viable source for a moderate levy that could generate significant income for the government treasury. But there was a critical issue: kerosene was an imported product, and China’s international treaties prohibited the levying of taxes on imports other than those collected by the Chinese Maritime Customs.

The new tax was announced at a highly volatile time in Chinese politics. Just two weeks earlier, Sun Yat-sen had died on March 12, 1925. On May 30, widespread strikes and demonstrations erupted across China following the killing of 13 labor protesters by British police in Shanghai. The unrest extended to Hong Kong in June, where a mass strike and boycott further disrupted trade between Canton and Hong Kong.

Despite the Canton government’s attempts to frame the tax as an inspection fee, oil companies and their home governments quickly condemned as an illegal surcharge on foreign imports. Specifically, British and American consuls called on oil companies to coordinate an embargo on sales to the Canton region.

Your Task

How should Standard Oil of New York (SOCONY), then the leading fuel exporter to China, respond to the new tax? As a historical consultant, you should prepare up to five slides to advise the company leadership. Specifically, you should address the following issues:

- What is happening in China and why does it matter? You should identify historical events, key actors (individuals or organizations), and relevant developments or processes. Do not just make a list; you must briefly explain who and/or what they are and how they help us understand the current situation.

- What are the main issues in this case, and why? Identify core scenarios, rather than facts.

- What should Standard Oil do, and why? Advise as to whether the company should join the embargo, and if so, how it should be implemented, but you are free to recommend other options.

You should draw on historical contexts and issues from class readings, lectures, and discussions.

To help you get started, please see attached a few documents that might be useful for your analysis. They include:

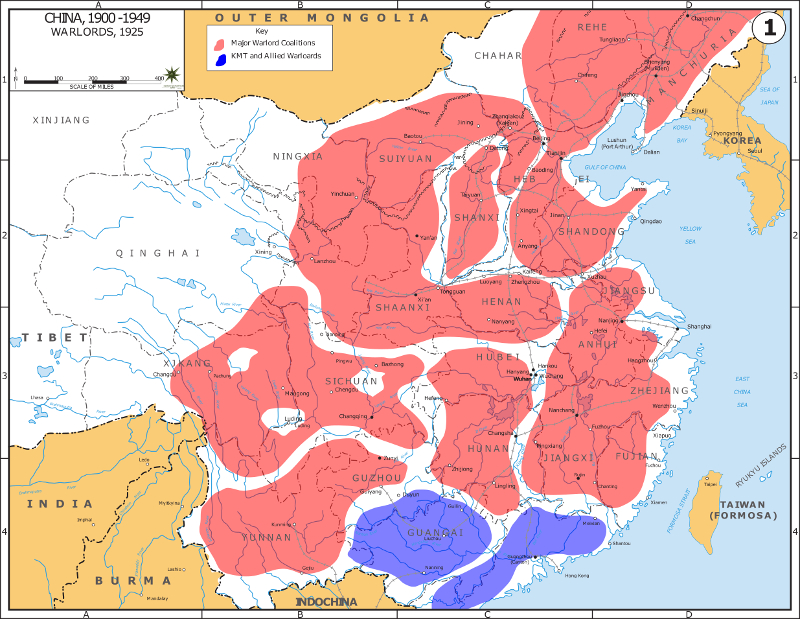

- A map of Republican China in 1925

- Background information on Standard Oil and the fuel sector in China

- The Nine-Power Treaty, negotiated at the Washington Naval Conference in 1921-1922

- Notes about an earlier deal in 1913–14 on Standard Oil’s rights to explore and develop oil in several northern provinces

- Press excerpt from The International Socialist Review

- Some statistics about fuel imports and US-China trade

Some general tips:

- Save enough time for thinking and writing. There might be more information than you need for your analysis.

- Produce clear and concise output. You may use various heading levels and bullet points to organize your slides, but you must write in full sentences wherever you present conclusions or qualitative analyses.

- Enjoy the challenge!

Sources

Map of Nationalist China, 1925

History of Standard Oil in China

In the early years of the twentieth century, as China remained almost entirely dependent on foreign sources of petroleum, one American enterprise shone particularly bright: Standard Oil. Unlike most of its compatriots, who relied on established European commercial houses operating in the treaty ports, Standard Oil took a more audacious tack. It built, at the cost of more than $20 million—its own modern and remarkably efficient distribution network.

Standard Oil’s strategy was elegantly simple: dispatch specially trained men into the Chinese interior, introduce an improved, and crucially, cheaper kerosene lamp, and watch the sales—and the company’s reputation—soar. By 1905, Standard Oil held over U.S. $18 million in total assets in Asia, an overwhelming majority of which was concentrated in China. The company had effectively created and then assiduously fed the Chinese market for petroleum products, primarily kerosene, becoming the largest American commercial interest in Asia in the process. Their Chinese name, “Mei Foo,” became synonymous with illumination itself, as kerosene lamps and stoves steadily replaced traditional vegetable oil as the primary source of light and heat for countless households. The company’s distribution centers for South China were in Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, success bred competition. By 1907, Asiatic Petroleum Company, a British-based subsidiary of the Royal Dutch Shell-Rothschild combine, emerged as Standard Oil’s principal rival. In a move straight from the playbook of Gilded Age titans, the two giants initially attempted to carve up the Far Eastern market in a classic cartel arrangement. But such divisions proved unsatisfactory, and competition raged throughout the 1920s. Despite the rivalry, these two firms together controlled approximately eighty-five percent of the kerosene trade in China. By 1924, this trade amounted to a staggering 223.3 million gallons, worth approximately $94 million. To put that in perspective, kerosene represented roughly 36% of the total value of U.S. exports to China, with the United States supplying between 70% and 83% of China’s kerosene imports. Consider Guangdong Province in 1924: of the 30 million gallons of kerosene sold there, Asiatic Petroleum sold 11 million gallons, and Standard Oil sold approximately 15 million gallons.

Source: Adapted from Wilson, David A. “Principles and Profits: Standard Oil Responds to Chinese Nationalism, 1925-1927.” Pacific Historical Review (Berkeley, Calif., etc.) 46 (1977): 625.

The Nine-Power Treaty, 1921-1922

Between 1921 and 1922, the world’s largest naval powers gathered in Washington, D.C. for a conference to discuss naval disarmament and ways to relieve growing tensions in East Asia.

The final multilateral agreement made at the Washington Naval Conference, the Nine-Power Treaty, marked the internationalization of the U.S. Open Door Policy in China. The treaty promised that each of the signatories—the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, and China—would respect the territorial integrity of China. The treaty recognized Japanese dominance in Manchuria but otherwise affirmed the importance of equal opportunity for all nations doing business in the country. For its part, China agreed not to discriminate against any country seeking to do business there. Like the Four-Power Treaty, this treaty on China called for further consultations amongst the signatories in the event of a violation. As a result, it lacked a method of enforcement to ensure that all powers abided by its terms.

In addition to the multilateral agreements, the participants completed several bilateral treaties at the conference. Japan and China signed a bilateral agreement, the Shandong Treaty, which returned control of that province and its railroad to China. Japan had taken control of the area from the Germans during World War I and maintained control of it over the years that followed. The combination of the Shandong Treaty and the Nine-Power Treaty was meant to reassure China that its territory would not be further compromised by Japanese expansion. Additionally, Japan agreed to withdraw its troops from Siberia and the United States and Japan formally agreed to equal access to cable and radio facilities on the Japanese-controlled island of Yap.

Together, the treaties signed at the Washington Naval Conference served to uphold the status quo in the Pacific: they recognized existing interests and did not make fundamental changes to them. At the same time, the United States secured agreements that reinforced its existing policy in the Pacific, including the Open Door Policy in China and the protection of the Philippines, while limiting the scope of Japanese imperial expansion as much as possible.

At the Washington Conference, the powers also agreed to permit the Chinese gradually to regain control over the customs and to permit the interim collection of a 2% percent surtax on imports and exports. This treaty had not been ratified by all the signatories, however, and as a result none of the decisions had been implemented. Foreign governments and businessmen steadily refused to allow local Chinese governments to tax their goods on the grounds that no changes in the treaties had yet been ratified.

Source: US Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/naval-conference

Standard Oil’s 1914-1917 Deal with Yuan Shikai Government

On February 10, 1914, the Standard Oil Company of New York (SOCONY) signed an agreement with the Chinese government. The contract granted SOCONY a one-year option to explore for oil in specific districts of Shanxi and Zhili provinces. During this period, China pledged not to grant oil concessions to SOCONY’s competitors in these areas. If commercial oil deposits were found, a Sino-American development company would be formed. SOCONY would own 55% of the stock, the Chinese government would receive 37.5% as payment for the franchise, and would have a two-year option to buy the remaining shares. This joint company would have an exclusive sixty-year right to exploit, refine, and market all petroleum from the provinces. The Chinese government also granted the company rights to build necessary pipelines and railways and promised its full support. In return, Standard Oil pledged to send experts immediately and to help China secure a loan in the United States.

Following the signing, SOCONY began geological work. After its geologists doubted the oil potential of Zhili, the company moved its operations to Shanxi. These operations were soon obstructed by the activities of a local bandit, “White Wolf.” The Chinese government then commandeered the company’s transport carts, stating they were needed by the army for bandit suppression.

Subsequent negotiations to establish the promised joint company revealed a fundamental disagreement over its scope. The Chinese government envisioned a large, nationally integrated oil industry, capitalized at up to $100 million, that would handle all aspects from production to marketing. SOCONY, however, conceived of a much smaller company, capitalized at around $1 million, that would only produce crude oil and transport it via pipeline. SOCONY intended to then refine and market the oil through its own, pre-existing distribution system, thereby protecting its profitable sales network.

In the summer of 1915, SOCONY Vice President William Bemis returned to China for further negotiations. He proposed a larger enterprise with an authorized capital of 100 million Mexican dollars. The Chinese government rejected this proposal, objecting to the plan for SOCONY to serve as the sales agent, the small initial capitalization, and the reliance on loans from SOCONY. They insisted on a national refinery free from foreign management control.

Later, Bemis indicated a willingness to concede on some points if the Chinese would substitute Hunan Province for Zhili and allow SOCONY to market the refined products. However, talks reached an impasse when the Chinese introduced new demands, including the right to fix oil prices and to split marketing profits evenly. Bemis called off the negotiations.

Through the mediation of American diplomat John V. A. MacMurray, negotiations briefly resumed. The Chinese Ministry for Foreign Affairs intervened and accepted a proposal similar to one Bemis had earlier supported. Despite this, Bemis adopted an uncompromising stance, accusing the Chinese of insincerity, and departed China without a new agreement.

SOCONY continued its exploration work in Shanxi and Zhili. By April 1917, the company concluded that these provinces lacked sufficient oil for a major commercial enterprise. By mutual agreement with the Chinese government, the 1914 contract was formally cancelled.

Source: Adapted from Pugach, Noel H. “Standard Oil and Petroleum Development in Early Republican China.” Business History Review 45, no. 4 (1971): 452–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/3112809.

Karosene and Gasoline Import Figures

Source: Table IX: Principal Commodities Imported From Foreign Countries, Statistics of China’s Foreign Trade During the Last Sixty-Five Years (1864-1928), p. 45-46

US-China Trade Figures

China’s Foreign Trade: Provenance of Direct Imports (Percentage Contributed by Principal Countries) (1919-1928)

Source: Table IX: Principal Commodities Imported From Foreign Countries, Statistics of China’s Foreign Trade During the Last Sixty-Five Years (1864-1928), p. VIII